Centuries of tradition have made many European winemakers very proud of their “terroir” – that is, the specific geographic and geologic conditions unique to each vineyard that give grapes a characteristic flavor when made into wine. One region with a rather unusual and celebrated terroir is the Mosel River valley in western Germany. The vineyards here mark the are some of the farthest north in Europe and perhaps the world, but winemakers have adapted to the cold and often cloudy conditions by taking advantage of the unique terroir.

As described in this article, the distinctively light and sweet Riesling that have made the Mosel River vineyards famous requires several elements for its grapes, all of them aimed at taking maximum advantage of the often-scarce German sun: the blue-gray slate heavy soil abundant in the region, which readily warms with the sun; extremely steep slopes, (the steepest vineyard in the world, with an incline of 65°, is here1) to catch maximum sunshine; south-facing slopes, for the same purpose; and adjacency to the river, for the sun’s reflection, as well as protection from frosts with river fog.

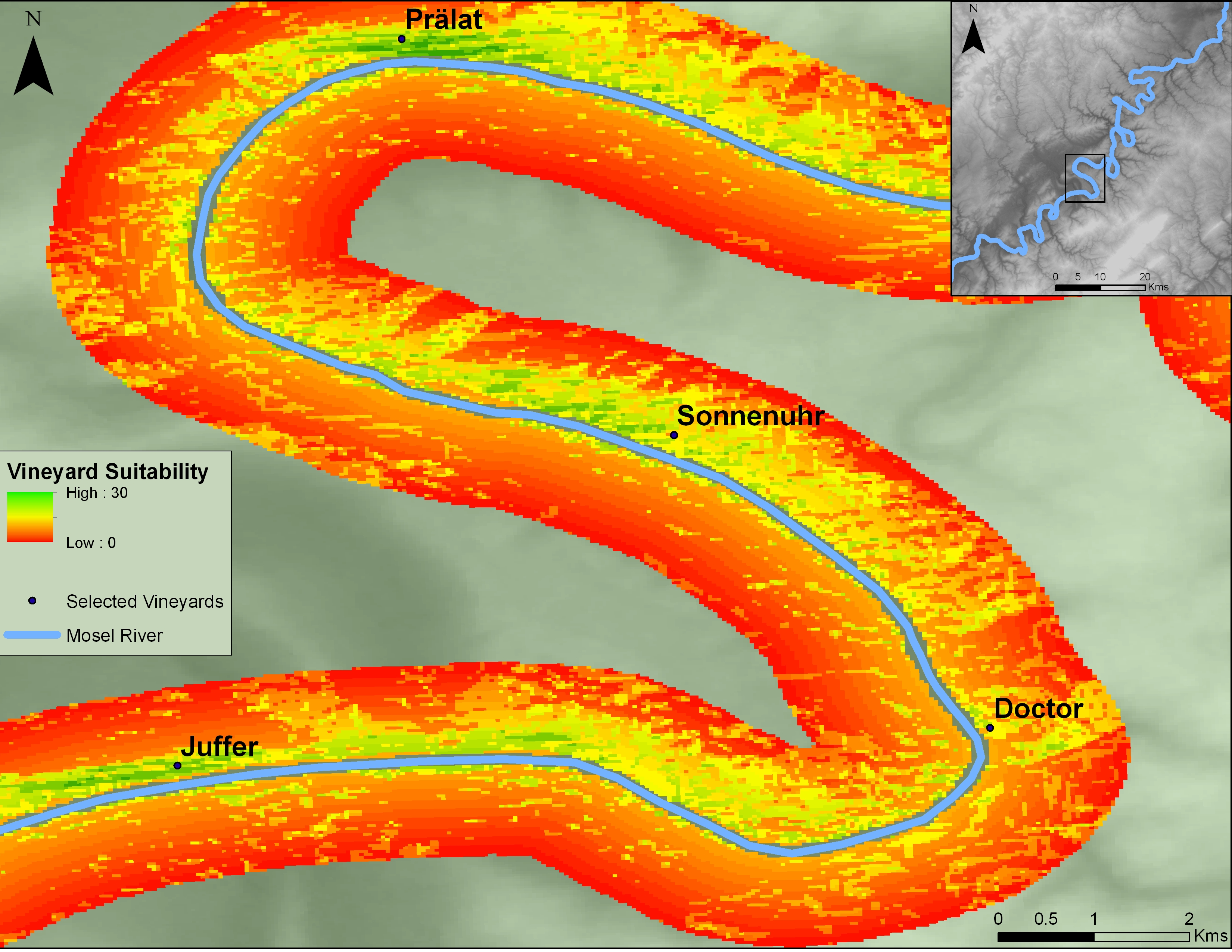

Spatial data can help us find many of these traits. Using spatial analysis with GIS software, these data can then be scored according to their suitability and overlaid with each other, which will reveal the places that have the best combination of desirable traits.

My aim was to model several of these criteria to find the most desirable land for vineyards along the Mosel river. Among these were slope, aspect (direction of a slope), and distance from the Mosel River. My model assumes the region’s slate soil to be equally distributed throughout the study area, which extends for one kilometer beyond the river.

A score of 10 was assigned to all areas 100 meters or less from the Mosel, with the distance score dropping by one for every 100 meters further away from the river, until the 1km limit was reached. Elevation data were then used to calculate both slope and aspect, with scores of 5 and 10 given to slopes of 30° to 45°, and 45° to 60°, respectively. Steeper and flatter slopes were given scores of 0. Finally, south-facing aspects were scored 10, while southwest and southeast aspects were scored 5. All other aspects were assigned 0 scores.

This scored data could then be combined into one suitability “surface” of data, snaking along the Mosel River, as seen below. To make this map more visually meaningful, the most productive section of the riverbank, the Middle Mosel, was focused on. The relative locations for a few of the most famous Mosel vineyards were included on the map for reference.

As the legend shows, the highest score possible, combining all three criteria, is 30. This is present in only a few tiny patches near Juffer in the south, with more surrounding Prälat in the north.

It’s not likely this map could be used to find suitable locations for new vineyards, because these have likely been long discovered and colonized through centuries of trial and error. But it would be interesting to compare wines from vineyards with different terroir scores, such as Prälat vs. Doctor, and see if the choicest bottles indeed come from the vineyards with a higher score on this map. That could confirm or dispel popular notions about terroir (which are not taken as seriously in the US as in Europe), and if confirmed, make a vineyard’s bragging rights a quantifiable measure.

1K. MacNeil, The Wine Bible, pg 532-535, Workman Publishing 2001