A chorus of groans echoed amongst the ten of us as we exited the truck on a muddy dirt road that served as the main highway along the Annapurna circuit. Dusk was falling, and we had been squeezed together in this vehicle for most of the past 12 or so hours. The day had begun in Kathmandu just before dawn, when our group, which had cobbled itself together at a hostel and through an online message board, clambered in the truck we had collectively hired to take us up the mountain. The ride was broken up by a long stop in a dusty town where our permits were slowly sorted out.

The truck had skipped the first three walking days of the circuit to get to the town we had stopped at, Syange. It felt like cheating, but we didn’t miss much. Houses and farms lined the highway leading to Syange, and there wasn’t much to look at. It had rained at times, and we passed other trekkers trudging through the mud.

The dimming view from our roadside lodging promised good things to come, however. A long, steep sided valley extended ahead, with a roaring river at the bottom. Standing on the hotel’s balcony, I could see banana trees growing below amongst the tin-roof houses – surprising, given the increasingly crisp November air at this elevation of about 3,500 feet.

After the rooms and roommates were figured out, we sat down for dinner and some planning. Maps were laid out amongst plates of dal bhat (lentils and rice), curries, and lemon tea. None of the planning mattered – tomorrow we’d get as far as we’d get.

A chilly first night was followed by an excitedly busy first morning of breakfast and preparation. After a hearty breakfast of banana pancakes and porridge, I got a message from my cousin on Whatsapp and gave her a call. She had completed the trek 21 years ago, and was shocked that the circuit now had wifi. Pretty cool, though the opportunity to disconnect would’ve been nice in its own way.

After packs were secured and water bottles filled, we were all, the ten of us, *officially* off! It was a fantastic first day to start. Sun peeked through clouds in the cool, humid air of morning. The group rapidly spread out along the trail, which was the same road we had arrived on in the truck. My cousin was amazed that this lonely mountain trail once only traveled by farmers, shepherds, monks, and the occasional eccentric adventurer had now been widened for vehicles, which were regularly trundling down the mountain, always accompanied by a plume of dust.

The map showed various side trails along the main one. Some of these were out-and-back paths that led to peaks, lakes, or obscure villages, and these were marked on the map in blue and blazed (marked on the trail somewhere visible, such as on a large rock) with white and blue stripes. Other trails split off from the road but still led “forward”, and these were blazed in red and white, as was the main Annapurna Circuit itself. I came across the first of these forks, “and took it” (as Yogi Berra might say), anxious to get off of the road and its dusty trucks and onto something built only for feet. I waited a moment for two of the party, Paul and Emma, to ask if they wanted to come along. Paul was having some trouble with his backpack, which was more like a suitcase with straps, so he certainly wasn’t interested in a steeper and slower path.

It was indeed steeper. Now that I was off the road, a near-tropical forest enveloped the trail from both sides. Who knew that a trail that led to the icy crown of the world started off in what was practically a jungle?

To add to my surprise, I passed a group of small schoolchildren headed up this narrow, boulder strewn path – no schoolbus here! A few minutes later, I entered a village, teetering on the side of this steep valley and accessible only by the path I was walking on. I passed the schoolhouse on my way down, and more students climbing up. Soon I was back on the dusty trail, having only taken the long way to get to where I now was.

I was convinced my detour had allowed the rest of the “party” to pass me, as I didn’t see anyone else around. In fact, I was alone on the trail for quite some time, except for the occasional jeep headed down the mountain. I crossed the river on a high swinging bridge festooned with multi-colored prayer flags, the first of many. A breeze whipped down the sun-drenched canyon, a welcome relief on what had become a sweaty day.

Soon the clouds returned, however, and as it always does at high elevations when the sun disappears, the temperature dropped fast. The canyon now opened up into a wide, stone covered floodplain, and a village emerged in the distance. I hoped to find my friends there.

Clockwise from Top Left: Your author on the first day of hiking, overlooking the Marsyangdi River valley. Ian, Jeka, and others on the long jeep trip up to Syange. River view from the lodge in Dharapani. A cliffside section of the trail on the first day, also shared by trucks. A typical swinging bridge, festooned with flags. Center: A tiny shop under an overhanging rock on the second day of hiking.

As it happened, I found three of them just finishing up lunch. No one had passed them – we were in the vanguard of the group, and I hadn’t fallen behind nearly as much as I thought. They waited for me to order a heaping plate of dal bhat and lemon tea, and after I ate, we were off. This group – Aksay, Marco, and Ian, affable fellows around my age from the UK and Australia – would be my sole traveling companions for the next two days. Marco, the chatterbox of the party, nicknamed the four of us the “Ninja Turtles”.

We continued a few more hours, following the river up the canyon on an increasingly cloudy and cold day. The town where we stopped for the night – I think it was called Dharapani – was noticeably colder than the nearly subtropical Syange. Up and up, but nowhere near the top. To be sure, it was a chilly night in our unheated room, but not as cold as the nights to come.

After a hearty breakfast of porridge with honey and instant coffee, and a brief panic that I had lost my phone, we set out again the next morning. Yesterday’s banana trees were today’s temperate forest. Big, stately trees – some kind of fir, perhaps – crowded along the margins of the valley floor, along the trail and up the slopes of mountains. They were a native kind of tree I had never seen before, and their presence here reminded me of Chinese paintings of mountain landscapes. This is really Asia, I thought. I’m in the middle of the biggest continent on Earth. It was one of those landscapes that really gives me the feel of a place, of its uniqueness in the world.

I turned a corner through a grove of trees, looked up the valley, and there it was. Ahead of me was the massive, pure white face of Annapurna II, at 26,040 feet the 16th tallest peak in the world. I had never seen a mountain like it. It was clearly very far away – every visible part of the mountain was glaciated, but since there was no ice or snow topping the other mountains on each side of the valley surrounding me, that indicated that even the lower slopes of Annapurna II were vastly higher than these local foothills. And yet, the mountain was so much taller than even that. I walked through a shrine with a set of prayer wheels, the first of many. It felt like a gateway to the Himalaya (Himalaya, by the way, is already a plural word that refers to these mountains – “Himalayas”, therefore, is redundant).

That night we bunked down in Chame, a larger (relatively) town at 8,500 feet of elevation, and noticeably colder. Since we were in the big city, the four of us decided to have a night out and hit the only bar in town, a smoky pool hall that offered no extra warmth.

Pool is very popular in Nepal, and I ended up playing a lot of it, along with Snooker, a billiards variation that I had not heard of until then. Snooker is played on a much larger table, and the game is quite different, with half of all balls red. It also has a points-based system of play, and I think the balls need to be pocketed in order. Either way, it’s much harder than pool and I was bad at it.

The trail continued through the forest the next day before opening up into a vast semi-arid alpine valley. Here the trail split, with a footpath continuing up the northeast side of the valley, through some Tibetan villages that could not be reached by vehicle. We decided to check them out.

The first stop was Upper Pisang, a town not far from the main road but built on the side of the valley. The town itself wasn’t especially traditional – our hostel was new construction meant to accommodate the growing number of trekkers. But above the town was a Buddhist temple, a weary few hundred more steps upward – tough going at the end of the day.

The temple was immaculately maintained, with the gold, red, and green trim on its roof and columns looking freshly painted. It was just as colorful inside, with an elaborate shrine to the Buddha amidst ornate designs on the ceiling and scenes from the Buddha’s life decorating the walls. Stepping outside through the doors revealed an incredible view of Annapurna, with the orange glow of the setting sun illuminating a gale force wind blowing snow off the distant peak.

That morning, I awoke with bits of ice floating at the top of my water bottle. However, the cold on this trail was really only ever a problem at dusk, when the remaining wood in a lodge’s hearth gradually extinguishes, and the trekkers around it gather closer and closer until the only option left to stay warm is just to go to bed. But in the morning, I’d be warm from a night in the sleeping bag, and in the thin, dry mountain air, the first rays of the sun were immediately warming no matter what the air temperature was. Checking my phone one morning, it was 27 degrees while I stood outside shirtless, but comfortable.

In fact, at midday I would often be downright hot, especially on this shadeless, increasingly desert-like stretch of the trail. I was cursing myself for leaving my sun hat behind in Kathmandu in favor of a beanie that was only useful at night.

Clockwise from top left: Our lodge in Upper Pisang. The temple above town. A view of the mountains in late afternoon from behind a temple column.

Signs of Tibetan Buddhist society became ever more apparent as the dry, rocky trail wound ever higher into the Himalaya. Along with the rows of prayer wheels (which I always spun as I walked past), there were now piles of slate rocks along the narrow trail with Tibetan script written on them. These are mani stones, a form of prayer created as an offering to the spirits of place.

We had lunch in Gyaru, a traditional Tibetan village of brick homes built on a series of irregular terraces connected by narrow footpaths. At the center of town was a wide-trunked, leafless tree that looked positively ancient, next to a shrine with a single, massive prayer wheel inside, painted red with gold Tibetan inscriptions circling it.

Finding an isolated lodge further down the trail with a nice patio and a killer view, we called it an early day that afternoon. This would also allow us to meet the rest of our wayward party the next day, who were a day behind but continuing on the more direct main road below. Besides, there was no need to rush. Despite the extra time to rest, the cold of night came too soon once again.

The next day, we entered the gates of Manang, a town of 6,500 that after so many villages, felt like a big city. multi-story lodges towered over the gravel-paved streets. All roads, as it were, led to Manang. As such, this was the first place that felt busy at all. Tour groups with middle-aged trekkers who carried their ski poles at all times had booked out the nice big stone lodge, and we were left with some cheap wooden shacks to bunk down in. Us four Ninja Turtles finally ended our journey as a singular unit as we met up with the other six we had arrived with. They seemed to me like people I had known a long time ago and only vaguely remembered. One’s perception of time always slows down when traveling. We stayed in Manang for two nights and made plans to take a two-day side journey to Lake Tilicho, one of the highest-elevation lakes in the world. I spent the extra rest day resupplying myself with a new jacket, taking a short hike to a hill above town with the rest of the group, and taking a tortuously cold shower.

Clouds began to build as our little side adventure began. The weather report showed a possibility for rain or snow, but we decided to go ahead. Better to get a storm here than continue the circuit and get caught without shelter while crossing the Thorung-La pass, the highest point on the trail, and a place where others have died from being caught in a surprise blizzard.

Clockwise from top left: View of the Annapurnas in the high desert on the way to Manang. Our lodge on the way to Manang. On a hill above Manang (left to right: Diarmid?, Otis, Marco, Rudi, your author). View of a Gangapurna Lake, a glacial pond from the hill above Manang. A long line of prayer wheels in Manang. A view of Manang and the Gangapurna glacier.

Early in the day, at the top of a muddy hill, we ran into a group of three or four that someone in our party, I think Rudi, recognized. They were led by a Brazilian lady whose name I can’t remember, other than that Rudi simply called her, “Brazil”. She was followed by some very quiet Chinese people who she simply called “My Chinese”. In a large group with at five or six nationalities, it’s funny the way we come up with shorthands for people.

Our now enormous group crowded into a multi-story wooden teahouse in the rather empty and forlorn looking village of Khangsar. The hot tea was welcome. With overcast skies blocking the sun, the temperature plunged in the thin air.

The trail snaked around the sides of the valley, which rapidly steepened, becoming more like a canyon. Around the final bend, a glacier came into view, with the mountain slopes covered in only gravel and patches of snow, not even a bit of grass. I imagined it was a bit like being in Antarctica, perhaps in the McMurdo Valleys, which are rocky, dry, and unvegetated, like this was. And at the end of the trail, across from the glacier, stood a huddle of three structures that was the Tilicho Base Camp, where we would stay for the night.

The next morning was cold, and the skies looked worse than ever. It was now or never to make it to Lake Tilicho before the inevitable snowfall came. The trail immediately headed upwards and never leveled off. We rounded bend after bend, spreading out without much chatter. Then the switchbacks came, back and forth, and ever upwards. Flakes of snow began to fall. My clothes were soaked with sweat from the exertion, but my feet and hands were still cold. I kept taking longer and longer breaks at each bend. If I was going to make it to this damn lake, I knew it was time to deploy my secret weapon: heavy metal.

Clockwise from left: The desolate landscape on the way to the Tilicho Base Camp. The trail to Tilicho crossing a scree slope. Our lodge at the base camp.

I don’t make a habit of listening to music when I walk, preferring to listen to the world around me. And whether it’s at work or hiking up the world’s tallest mountains, I save my best songs for when I need the most motivation. I put in my headphones and on my iPhone played one of my favorite albums of all time, Lore, by Elder, a heavy psych/doom metal band. My fatigue melted away and I was transported to a fantasy land, marching to battle as an ancient warrior clad in armor and furs and wielding a broadsword. The falling snow and the stark, rocky landscape, here on the roof of the world, could not have provided a better setting for my imagination.

Finally the trail opened up to a plateau, and the falling snow turned into flurries. After a change into drier clothes, I hiked the last few minutes to reach the lake – or what I could see of it, anyway. The snow had obscured the million-dollar view of Lake Tilicho and the mountains surrounding it. But I had made it, and just barely, before conditions deteriorated further. I waited for others in my group to arrive, but after high-fives and a few pictures, it was time to head back. The snow wasn’t letting up and we were getting cold.

Left: Getting changed in freezing temperatures on the way to Lake Tilicho. Right: Lake Tilicho as the snow began to fall.

A well earned lunch awaited us back at the lodge. Suddenly Brazil burst in, exclaiming, “We have a problem!”, in what became our party’s longest running in-joke, and the name of our WhatsApp group. And I don’t actually remember what specifically the problem was, but I think it was the fact that the trail to get back to “civilization” was heavily snowed in and possibly dangerous. Or maybe the fact that we couldn’t stay there – all around us, the Nepalese cooks were packing up to leave as well. We were the last trekkers to be there before it closed for the season.

No way around it, though – we had to leave, and quickly. We finished up lunch, put on all our warmest gear, pulled some microspike straps around our hiking boots, strapped in to our packs and marched off into the falling snow.

There’s never much danger of losing your way on the Annapurna trek. There’s not enough vegetation to overgrow the trail, and it’s always pretty obvious which way you should be going – in this case, along the side of the canyon – just don’t fall off. So the snow was not much of a problem in terms of covering the trail. The biggest issue was slipping. Here, the microspikes and our ski poles really paid off. Other than that, there were a few inclines to take slowly, but none terribly steep. And by mid-afternoon, the sky had cleared, revealing a beautiful snow-covered valley behind us.

We stopped at the first lodge we came upon, which was on its own, away from any town. As one of the few places to shelter along this trail, it concentrated everyone coming from Lake Tilicho as well as everyone who had been headed there before the snow began. Real estate by the hearth was at a premium, not only for people but also for their wet socks and boots. The lodge room was filled with chatter about conditions both ahead and behind us – the kind of necessary exchange of news that is now rare in the age of internet and smartphones.

It was late by the time I got dinner – the poor lodge staff was overwhelmed by the number of orders. Afterward, it was an icy, dark night of sleep in a cold, stone room that felt a bit like a castle dungeon.

A long day awaited us the next morning. First we hiked back to Manang, where snow gave way to gravelly mud on a warmer day filled with sunshine. After briefly resupplying, we left town again, this time to the north. This was the final stretch of the trail before the Thorung-La Pass, elevation 17,769 feet.

The day’s hiking was a few more miles of trudging through the mud, which turned into a ridge above a small river valley, which eventually led to a precipitously steep hike down to a bridge, and then up again the other side. Snow reappeared on the ground as we ascended, and when we finally tumbled into the first lodge in the village of Yak Kharka (true to its name, there was a Yak head with glowing eyes on the wall), I was reminded of a ski resort by how much snow it was covered in.

Clockwise from top left: Looking back at Manang on the trail leading out of town. The glowing-eyed yak head in the Yak Karka lodge. A bridge crossing the highest reaches of still-liquid water in the valley. A small snow leopard (??) or a big house cat guarding the trail from Yak Karka to Thorung Phedi. Approaching Thorung Phedi. The Yak Karka lodge complex.

We took a long lunch the next day at Thorung Phedi, a small base camp placed just before a steep series of switchbacks that lead to the Thorung La High Camp. This was to wait for others, enjoy the scenery, but mostly to steel ourselves for the brutal hike ahead. By distance, it was only one kilometer to walk, but that was with a 1,000 foot climb. We were in the thin air of 15,000 feet already, and feeling it with every step. Time for another round of heavy metal to push me up the mountain, I thought, as I dug around my bag for earbuds.

The ground felt permanently frozen at the High Camp. It was dark, as the camp was deep in the afternoon shadow of gargantuan mountains on both sides. The lodge buildings were old and forlorn, and the rooms felt more like cells. I tossed my bag in and proceeded to make a quick hike up a snowy, steep hill I had seen on my way into “town”. I carefully made my way up a narrow ridge of snow and ice to a little flag-festooned shrine on top. From there, I looked back the way I had come that day to see the impossibly high wall of mountains on the other side of the valley. Now I was eye-to-eye with their snowcapped peaks, with even more beyond, where the icy white tops of the highest Himalaya mixed with clouds. Now I could really see why this place was called “the roof of the world.”

Back in the ramshackle lodge, a low-ceilinged wooden structure, I struggled to place my dinner order among the throngs of trekkers crowding the only heated space in the camp. The furnace was draped with socks and surrounded by boots, and forget about finding anywhere near it to sit. I think a few of us pored over a map at the table to come up with a plan for the next day, for which timing would be more important than ever. Between the high camp, the pass, and several miles down the other side of the mountain, there were no lodges. No food, no water, and no shelter. Better make it over the pass.

I endured a brief, but frigid and relatively sleepless night at 16,000 feet, frequently waking up from pseudo-nightmares that I think were a result of my oxygen-deprived brain panicking in the thin air.

Breakfast had never been earlier, and I think our group was off by about 7:30.

There was a sense of palpable excitement as our group trudged up the icy trail in the frigid, dim light. It wasn’t particularly steep, but every step was an effort at this elevation. Up and over one glaciated hill and on to the next, I began to get a sense of, “are we there yet?” But of course, there’d always be one more hill. I decided I’d need some music again to make this final push.

And then, in the middle of one particularly churning riff from Samsara Blues Experiment, there it was. The top of the Thorung-La Pass, and the highest point on the Annapurna Circuit.

High fives and hugs all around for our group as we cheered each one that emerged at the top of the hill. This was followed by picture in front of the sign, covered with more flags than a circus tent. After an hour or maybe even two at the top, and one more short walk up a small hill to get a view at the snowcapped peaks behind, I began to feel a little queasy. At long last, the elevation had finally gotten to me.

Left: At the top of the pass. Nice place for a tan. Top Right: Near the top of the pass, looking back on the icy landscape. Bottom Right: (from left: Me, Brazil, Jeka, Diarmid, Rudi, Ray)

The cure was to go down, and that was now the only way left to go.

The other side of the pass was like another world. The snow and ice of the past few days gave way to a rocky desert, in the rain shadow of the Annapurnas now behind us. Another high range of mountains lay in the far distance, but only their very tops had a bit of white at the top – the rest was brown.

We dropped thousands of feet in mere hours as the trail switchbacked precipitously downward. My microspikes, which I still had on to keep from slipping, were getting mangled in the rocks, and my knees felt like they were too. A worsening headache became splitting, even as I drew more oxygen with every breath as I descended. I guess there’s a lag time when it comes to elevation sickness.

We passed a series of strange blue huts on the way down, which appeared to be little more than shipping containers bolted to the ground. They were filled with trash and smelled awful inside. Someone explained to me that these were emergency shelters installed in the wake of a disaster on the trail in 2014 in which a cyclone moving north through Bangladesh brought an October blizzard. 43 people died in the storm including 21 on this section of the Annapurna circuit.

It’s hard to say which would be worse, braving a deadly snowstorm or the smell inside one of these things.

I was just about last off the trail that day. I’m not the fastest at downhill hiking, as my knees get really jangled by the downward force, and I can be prone to slipping. But there was no rush, as a huge group of us tired, dusty trekkers took a long break at the first restaurant we could see in the valley below, taking up every seat and surface in the courtyard with our bodies and gear, as the family of restauranteurs rushed to make enough Dal Bhat for the lot of us.

Muktinath was the first town on this side of the pass. We walked through a park with planted trees and a canal with running water. Signs of real civilization seemed alien after so many days spent in lodges that would not exist except for the trekkers staying in them. But here was a town that predated the trail. I passed by a Buddhist monastery that advertised the going rate for anyone who wanted to stay there as long as they had “spiritual interest”: the equivalent of about $50 a month, and $500 a year. Beats renting anywhere in the US.

The hottest spot to stay in town was Hotel Bob Marley, which was a proper hotel, with three stories and many rooms. I was excited that I might finally have here some of the comforts of modernity, but it was not so. Our basement room was as cold as anything on the mountain, and the few bathrooms had only a trickle of ice water. Still, I managed to take a painful shower.

Dinner that night was a celebration and a final reunion, for both our group of ten or a dozen people, as well as some others I had seen on and off along the trail. We ate at a big table together and said our farewells for those who would be expedited by four-wheel drive bus to Pokhara, Nepal’s second city and the end of the trail for anyone finishing up Annapurna.

I wanted to continue on to Kagbeni, a town that was essentially the gateway to Tibet. It was possible to trek beyond this, into a region of Nepalese Tibet known as Mustang, but a special permit was required to go that far. Also, Kagbeni had a lodge and restaurant called “YacDonald’s”. How could we miss that?

Only a handful of us continued the trek, which followed a road that was, of all things, actually paved in some places. After soup at a neatly-kept roadside restaurant with a courtyard, we said goodbye to a few more friends who got a ride with a jeep headed back to the city.

And then there were three.

Aside from me, my companions were Rudi, a 19 year old Australian who had been with the original group of ten I arrived with. He hadn’t been one of the Ninja Turtles vanguard at the beginning of the trek though – he was with the slower group a day behind us.

That slower group had met Diarmid, a wisecracking Irishman in his late thirties. Diarmid joked about everyone, but to him I was “The Knower” – I suppose because I filled the hours on the trail with pointless facts and trivia to whomever would listen.

“I feel like we’re on patrol in Afghanistan”, Diarmid said, as we rounded another corner overlooking the dry, rocky river valley before us, as brown as the towering mountains on the other side. It did indeed look like pictures I’ve seen of Afghanistan, which after all was on the dry side of the Himalaya, as we were here.

Across the river, and nestled against a steep foothill was Kagbeni. The hill we stood atop offered a good view of the pleasant-looking town below, dominated by a large, colorful temple in the center.

We descended the switchbacked dirt road leading down to the city. Prayer wheels and a stupa greeted our entrance to the narrow, cobblestoned streets set between houses built from river rocks and covered in mud. Kagbeni had an authentically Tibetan feeling to it I hadn’t quite seen since the off-road side route in Pisang. And those were small villages – here was a proper town.

We found the yellow arches of YacDonald’s. The hostess showed us some rooms before requesting I clean off my shoes. Looking down and back, I realized I had tracked in an *absurd* amount of animal (Yak?) poop all over the lodge, including the hallways and multiple rooms. I sheepishly tried to wash it off my shoes before just leaving them outside. God willing they wouldn’t be stolen, or I’d be stuck here forever.

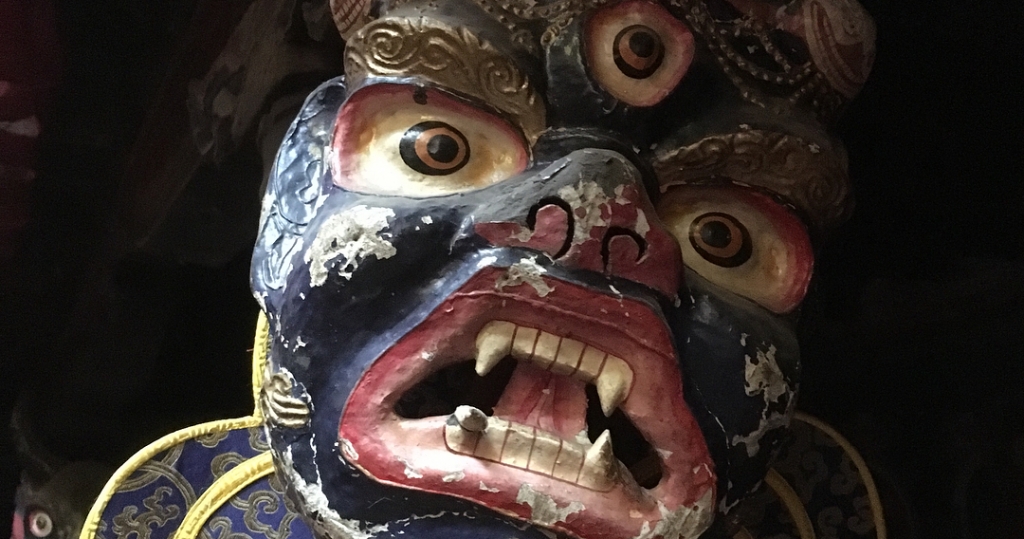

We took a tour of the temple, or gompa, which stood on the grounds of a monastery. Young boys in maroon robes played in the courtyard, while a monk in a matching robe led us into the gompa. Colorful ribbons, flags, and other fabric covered the ceiling and walls in a kaleidoscope of patterns and Tibetan script. Masks with bizarre and frightening faces were hung from each column inside the gompa. I believe they were meant to represent evil spirits, but perhaps also to ward them off; regretfully I can’t remember the details of everything the monk told us.

The gompa was built in the 15th century, and to be honest, this was believable. The wooden floors and walls were rutted and pitted. Behind the Buddha which sat serenely at the altar, I saw a rat scurry past.

monastery.

As if to prove its lineage, the monk showed us the crown jewel of the temple, a book that he claimed was written by its founder six hundred years ago. It sat inside a glass case, a single large Tibetan letter visible on an open page. It looked like it might blow away into dust with even the slightest touch.

We paid a donation to the temple and walked back for dinner at YacDonald’s, which had similarly crazy masks of monsters and animals festooning the walls of the dining room. Still paranoid from tales of food poisoning, I stuck with my vegan diet and had a veggie burger instead of Yak – regardless, it was perhaps the tastiest veggie burger I’ve ever had.

Even Kagbeni was not without a snooker hall, and after dinner we played an interminable game that was stalemated by our own lack of skill at this much more difficult version of billiards. Eventually we started playing cooperatively, working each ball closer to the hole in the hopes that someone would pocket it, until all of a sudden I made two one-in-a-million shots in a row that I am still impressed by.

As I recall there was one more small town deeper into Mustang that one could visit without a permit. I can’t remember what I hoped to find there, but there wasn’t much. The village temple was locked and no one was around when we took a short day trip to it the next day. Arriving back in Kagbeni in mid-afternoon, there was still time to make it to Jomsom, a large town and transportation hub for the region. There, by plane or bus, we would finally get back to Pokhara and meet the others.

I guess “still time to make it” is relative, though. Wanting to get off the dusty road and its accompanying jeep traffic, we opted for making our way around the rocks in a wide, dry riverbed next to it. This became especially tricky as night fell around us. I looked for a way up to the road, but it was now too far up a steep bank to reach. Fortunately, the faint lights of Jomsom appeared in the distance, and we were able to make it to the city guided by our flashlights.

Jomsom is a town built for function. Dominated by ugly concrete block buildings, it has a bit of a wild west feel, with a wide dusty main boulevard separating two lines of dingy shops. We found an open lodge, and were the only guests sitting down for dinner in what felt like somebody’s personal kitchen.

There was talk about how we should proceed from here. We could fly to Pokhara, which Diarmid seemed most interested in, but this felt like cheating to me – to say nothing of the dismal flight safety record in Nepal. There was also a day-long bus back to Pokhara, and I had heard something about downhill mountain biking to get back.

I was surprised to find out that practically no one continues walking south from Jomsom. I suppose that even the most vacation time-endowed Europeans don’t have forever to do the full circuit. Many people may also assume that once you’re over the pass, the way back, through the lower Mustang valley, appears in terms of scenery to be very similar to the beginning of the trail.

In the end, we went with the bus, which felt a bit anticlimactic to all of us, I think. To make matters worse, it was the roughest bus ride I have ever been on, and that includes overnight trips on dirt roads in Bolivia. Here the road was often more like a wide mountain trail, steep and full of loose rocks. The bus had four wheel drive and very high clearance, but even so it was like being on a jackhammer with wheels. Looking outside, it was a perfect sunny day as we descended – first through the high desert, and then back into the temperate forest, the snow-capped Annapurnas peaking through, this time to the east. We passed a few trekkers and I felt like joining them.

We stopped for lunch at a roadstop cafeteria, now practically back in the jungle, and I got a pile of greens for the first time in a while. There wasn’t much trail left, but I felt like just deciding then and there to walk back. I decided it would be silly at this point, however.

Not long after lunch, the bus stopped at a roadblock. I can’t remember if it was a landslide being cleared or just a pile of dirt from construction, but either way, it was obvious this was going to take a while – hours, perhaps.

Looking at the map, I saw where I thought we were, and what appeared to be a trail – the thinnest line allowed on the map’s legend – extending from where we were in to the mountains. From where we were stopped, I could see a swinging bridge going across the river gorge. Was that the trail?

I floated the idea, and found my companions, Diarmid especially, had the same FOMO on more adventure as I did. We had one last chance – why the hell not?

After a few more minutes of hyping ourselves up, we set off. There was little time to lose. It was already four in the afternoon, and we had only a few hours of sunlight left to reach a hypothetical village I could see on the map.

The bridge across the gorge led to steps that led precipitously upwards, into the foothills. Up and up they went, as twilight was already beginning to set in and I began to wonder if this was such a good idea. Worse, the trail began to fork, and we had to guess which might be the way. Taking a turn off the ever-rising steps, the trail turned into what looked like a dry rice terrace. I soldiered on, but Rudi, our 19 year old voice of reason, began to get irritated and argued we at least get back to the steps. I always hate returning to a fork to go the other way, but it made more sense than wandering around this terraced farm.

So we continued onwards and upwards, now in total darkness, illuminated only by our headlamps. I heard a strange sound in the bushes, almost like a growling cat. I don’t think there were any here, but my imagination was certainly running wild at this point.

Finally: a dim light shining off to our right. It was a farmhouse. We walked over in the hopes that someone knew the way to the village on our map, or any town at all for that matter.

We found a woman in the back of the house and tried to announce our presence as gently as possible, but she seemed shocked and even a little scared at these most unexpected visitors. Nevertheless, she led us back into the house to meet with her husband. Neither of them spoke more than a few words of English, but eventually he offered to lead us half a mile to the nearest village.

We followed the farmer in the dark, across rice paddy terraces, unsure of what lay ahead. Finally some houses appeared out of the dark, and we were in the middle of a small village square.

It was only about 7pm but it felt like midnight. The village had been quiet, everyone settling down for an early night, but our strange presence woke them all up, and they came outside to gawk. The mood was more incredulous than irritated, but we felt pretty sheepish, and rightfully so, of course.

Eventually we thanked the farmer and bid him adieu. Very few in the village spoke any English. I think there was one man who did, who might also have been the mayor. He found someone with a spare room and led us back to her house. The room, thankfully, had exactly three spare beds. It also had rat poop on the sheets, and the corpse of the animal that likely produced it.

However, our luck, and our moods, improved with dinner. The hostess cooked a massive dal bhat for us, with new kinds of chutney we had never tried before. While cooking our meal, she occasionally broke into laughter at the absurdity of our presence and the ridiculousness of the whole situation.

My sleeping bag liner was certainly a welcome addition to my bedding in the dead rat room. But we managed to sleep. There wasn’t much to eat for breakfast in the morning, just some lemon tea and a few bananas. We paid our hostess much more than was asked and were then on our way. I’m still grateful to her and the whole village for their incredible hospitality in the face of our reckless little adventure.

Someone, probably again the mayor, gave us directions. I’m terrible with following spoken directions on the best day, so fortunately Diarmid paid better attention. I still had faith in navigating with the map, though if the village we had stayed at was actually the one I believed it was on my map was still just a guess.

Off again we set, although I had a bit less spring in my step than most mornings, due to a very minimal breakfast. In the light of day, I could see that the village was set on a verdant hillside with jungle-like vegetation. We left town and passed several more farms set in the dense underbrush, until it was just us three and a stony, wet trail hugging the steep slope of the foothills.

The trail reached the back of this valley/canyon, crossed a small stream that required some stone hopping, and continued up the other side, more steeply now. We asked some passing schoolchildren (what school could they be headed to??) if we were headed towards…something, and they replied in the affirmative, for whatever that’s worth.

Then the trail turned to steps headed into the forest and straight up the mountainside. That banana and lemon tea for breakfast a few hours ago was not doing me much good now, if it ever did. I was reminded of climbing the Inca steps up to Machu Picchu, another precipitous morning climb through a tropical forest. “It feels like we’re soldiers marching in Vietnam”, Diarmid said. From Afghanistan to Vietnam in three days – that’s Nepal, I guess.

After what seemed like an unending series of false summits, the trees began to clear and we were mostly atop a ridgeline with some houses nearby. Houses meant food, so I was scanning each one to determine if it could, by any interpretation, be a place that would serve us lunch.

No such luck. We continued up the ridge past a few scattered farms until coming across some new construction. Walking inside a mostly finished two story building, we found some boxes of snacks and chips, and eventually an owner. This store wasn’t officially opened yet, but we still got some ramen noodles and many plastic wrapped packs of cookies for lunch. It still wasn’t much, but enough to keep us going.

The trail continued as a country road lined with farmhouses, and the ridge turned into a plateau covered in fields. Dust and the smell of cattle filled the air. After another hour or two of this, and the occasional view of the now far off peaks of the Himalaya, the trail turned into a temperate piney forest, much like the one we had passed through on the second day of this journey. It was a relief from the shadeless, dusty countryside.

We snaked gently upwards through the trees for the rest of the afternoon, until finally emerging from the bushes to arrive at our destination: Poon Hill.

At the top of Poon “Hill” (elevation 10,531 feet) is a viewing tower, paved terraces, and railings, all looking on to a 180-degree vista of the highest peaks of the Annapurna region, complete with interpretive signs. It was the most developed tourist site I had seen in my entire time in Nepal, and it was filled with people. Tour groups, day trippers, elderly Europeans with freshly-purchased nylon “outdoor gear” – the gang’s all here.

I felt like we had stepped out of a fever dream back in to some kind of ordered reality that I had not yet seen anywhere in Nepal. To go from stumbling into a hillside jungle village at night, to a scene that could have come straight from Switzerland the next day, was jarring to say the least.

No one else had arrived to Poon Hill from the side of the mountain that we had. They had all come from a long set of paved steps that led down to the town of Ghorepani, which looked like an Alpine ski village. We checked in to a multi-story hotel before feasting like never before in the cafeteria below. All dietary bets were off, and I had no fear of piling my plate with roast chicken, the first meat I had consumed as of yet in Nepal, among many other delectables.

The next day was the home stretch, but we still had a long way to go. We set out at about 8:30 or 9, and the trail leading out of Ghorepani was already crowded to the point of being nearly impassible at times. Time after time, we’d get stuck behind a 20+ person tour group until the entire line of them stopped and let us pass. Better not stop to take a picture of the glorious morning views, or they’d catch up again.

Things evened out when the mostly flat, paved trail gave way to a rocky scramble into gullies and ravines surrounded by temperate jungle. The day’s hike consisted of a lot of up and down sections, and after two and a half weeks of this, I was really feeling it in my legs. Looking up at yet another set of endlessly snaking switchbacks heading upwards into the woods, I sighed and put on my music one more time to push through it. At the top was a cluster of lodges and restaurants, and we settled down for one more lunch on an outdoor terrace under cloudless blue skies, overlooking a green valley below.

I still had a week and a half before my flight out of Nepal, and I had been musing about continuing my trek to the Annapurna Sanctuary, a high altitude basin forming the crown of the Annapurna mountains, in the center of the circle we had just made with the Circuit. The trailhead was here, and by my reckoning, I had just enough time to do it and get back to Kathmandu in time, fully maximizing my trekking time in Nepal.

My heart wanted to go on, but my legs didn’t. I continued with my friends down into the valley. “So you’re done chasing the dragon?” Diarmid mused, with one of his many colorful Irish idioms.

I got my last looks at the snowcapped peak of hyper-prominent Machapuchare, or Fishtail Mountain, behind the jungle-clad foothills that increasingly obscured the view of this peak. We descended into the hillside town of Ghandruk, deftly avoiding cow patties as much as crowds of tourists headed upwards. They had a long way to go – maybe I was glad I didn’t anymore.

Perhaps another mile out of town and there was a dusty staging area for trucks headed out of the mountains. We got aboard one for the three hour ride into Pokhara, a lovely lakeside city with views of the Annapurnas on a clear day, and the perfect place to end a trek. Here the three of us reunited with our wayward trekmates who had taken the short way down, for a few days of feasting and lazing about until we decamped to the same Kathmandu hostel that most of us started at, for a week of more of the same, including a viewing of the new Star Wars movie, a Christmas dinner, and lots of billiard games. By coincidence I was on the same flight to Bangkok as two other trekkers, (three after Paul joined us at the last minute) and we continued to hang out there for a few days more before going our separate ways.

Left: One last look back at the Annapurna Himalaya from the city of Pokhara. Right: Kathmandu.

My trek in Nepal was a profound experience that I’ll always be wishing a return to. Contemporary travel is so often dictated by schedules, reservations, fast mechanized transportation of various kinds, tour groups, and canned experiences. It’s not often that you get to travel like the Hobbit, where all that’s needed is a backpack, your feet, and a few dollars for supper and a place to sleep at the next inn, where you’ll be reunited with fellow travelers. And if you get split up again, no worries – you’re all part of the same journey.

All of this, of course, is set against the backdrop of the perennially snowcapped peaks of the tallest mountains on earth, ancient temples and villages, and inhabited by lovely people from all of Nepal’s various cultures.

I might be “chasing the dragon” forever.

Note: the photos in this post were taken by me, Jessica Abejarias, and perhaps also some other people from my trek…thank you all for letting me borrow your pictures to illustrate my story!