The Indo-Pacific “coral triangle”, roughly defined by Thailand, the Phillipines, and northern Australia, is the most biodiverse coral eco-region in the world. And in the center of it, at the western end of the Indonesia half of the island of New Guinea, is Raja Ampat – a string of limestone archipelagoes with a marine biodiversity so great it might be considered to be the coral triangle of the coral triangle.

It is not easily visited, which is good so impact stays low. Often the only way to visit remote coral reefs such as this is on a scuba diving cruise. I’ve been resistant to becoming certified to scuba dive, but I am a freediver. With mask and fins, I can dive and simply hold my breath while I enjoy the underwater world. My depth record is about 80 feet, and it’s impossible to say how “long” I can stay underwater – it all depends on muscle exertion.

When I had the opportunity to join a rare freediving cruise to Raja Ampat, I jumped on it immediately. Ever since I was a kid and my family and I took snorkeling trips to John Pennekamp State Park in the Florida Keys, I’ve been fascinated by the tiny alien planet that is a coral reef ecosystem. It’s incredible how much life one can see in a coral garden – from fish as giant as a whale shark to as tiny as a bright blue guppy hiding in the crown of a coral head to hide from being eaten. And there’s everything in between, from colorful sea slugs to waving sea fans to bright-lipped giant clams, which appear to “blink” as a diver approaches. And all of this lives upon the reef itself, a multi-textured, multi-hued psychedelic landscape of corals in an endless variety of shapes. Some appear massive and round, like boulders; others branching like trees; still others and flat and stacked like plates.

I flew from Bali to Sorong, a rough-and-tumble city serving as the capital of this region. After a beautiful flight in which I caught a glimpse of some of the coral-fringed islands we’d be sailing into, my trip began rather inauspiciously.

The taxi driver ripped me off, the toilet in my rundown hotel had no water to flush, and I felt eyes on me in the muddy street, the first time I felt possibly unsafe in my travels through Asia. At lunch by the waterfront, an old man drunkenly tried to have a conversation with me in broken English. I humored him until his friend dragged him away. That night, I met up for beers with the freediving guide, Kwab, and a chainsmoking Frenchman, Pierre, at the nice hotel in town, which I probably should have sprung for myself.

The next morning, I got to the ferry port after being taken to the wrong one at first and waited a few anxious minutes for the rest of the crew, who were arriving from the airport and just in time before departure. The ferry took us to Waigeo, a large island a few hours away, from which we’d begin the voyage. SUVs on the island took us to a scuba camp where the boat was docked. Our boat was a trimaran, a custom-built eco machine built by the salty Aussie owner, Rod. It was built to sail and run on solar power, although ironically neither of these were ever used on our trip. The interior was lined with bunks with the kitchen in the bow, and two bunks out back. After a few hours of loading and final preparations, we were off, with local kids waving at us as we sailed away across the crystal blue water we’d see for the whole trip.

The first stop was a small but inhabited island called Friwin. We suited up for the first time and dived in maybe just 50 yards from the beach. It was a shallow snorkel through big, mostly healthy looking hard corals that was immediately the best off-the-beach snorkel I’d ever done. All of a sudden, Toni, a Spaniard dive instructor working in Malaysia, frantically waved and pointed below. Perhaps 20 feet deep, underneath a big coral bommie, he saw a Wobbegong – a funny name for a funnier looking shark. It lies flat on the bottom, mostly hidden under sand, with tendrils forming a “beard” around its mouth, I assume to attract unfortunate fish.

Further down the reef, I found some anemones guarded by clownfish – but these were redder and bigger than the clownfish in Thailand, and much braver – they attempted to chase me away from their homes!

We took the tinders (baby trimaran motorboats attached to sailboat mothership) over to a neighboring island with a steep cliff dropping into the ocean. This was our first wall dive. Colorful sponges and a few corals attached to the rocky surface of the wall, and multiple schools of fish of many shapes and sizes swarmed above the deep coral garden at the end of the island. I couldn’t believe this was just the first day.

We motored along the shore of the large, sheltered bay Waigeo forms with its southern neighbor, dotted with the same mushroom-shaped hills and islands that characterised the landscape of Thailand and Malaysia. Finding a shallow cove sheltered by a small island, we anchored for the night. A few of us took stand up paddle boards to row across the glassy and darkening water, around a bend and into another bay. Here, the sun set behind purple clouds and dark green hills from which the squawk of a tropical bird occasionally emanated. Other than that, the distant sound of other paddlers across the bay was all I could hear.

That night, one of the passengers, Maria Alejandra, an apparently famous Colombian actress who owns a theater in Bogota, regaled us with a story over dinner about a production she managed that covered the atrocities committed, mostly by right-wing paramilitaries, in Colombia’s long civil war. Many of the performers were victims themselves, and telling us all this brought her to tears.

Day two began with another paddle around the small limestone islets in our anchorage before we motored out. As Rod put it, the plan was to cruise “African Queen style” through a section of tall limestone islands on the other side of the bay, on our way to a narrow strait between the two main islands that formed this bay. These funny shaped green islands, like towers sticking up out of the water, were what I imagine the famous Ha Long Bay in Vietnam to be like – without all the fanfare and people.

We came to the “mouth” of the strait, which is probably better imagined as a river of sorts. It was extremely narrow, never more than 100 yards wide, and the ocean’s tidal flow through this narrow passage could be strong. We took a tinder “upstream”, and this really had the feel of a jungle cruise – green rainforest clinging to porous limestone cliffs on both sides of a crystal clear blue “river”. Once we got in, the “ocean river” effect became even more surreal – here were colorful sponges, corals, and sea fans growing underneath the overhanging limbs of leafy green trees, as if they were in the Amazon! We floated downstream with the current, past a huge bugeyed puffer fish, so large it had remoras attached to its belly, and into a shallow bay with a coral garden, with tiny fish dancing upon the crowns of hard corals, with some of the blue and orange christmas tree worms attached. Someone discovered a small arch to dive through that led us back into the deep river, and past a school of yellow tailed barracudas deep underwater. On the surface, Kwab beckoned us toward something on the side of the rock – a cave! Small crabs skittered around the rock at the entrance. Once inside the darkness, blue light reflected upwards from the river, emanating a faint turquoise glow on our faces and the walls of the cave. A small passage led to an opening up above where the forest could be seen. Within a second cave, and below another opening to the jungle, a small patch of coral grew on the muddy bottom. This combination of coral, growing inside a dark cave, which was itself inside a rainforest struck me as almost absurd. What an incredible environment.

I shot downriver with the fast moving current, into a wider area of the river surrounded by more limestone spires towering above. The tinder was on its way to pick me up, but one last peak underwater and I saw a black tipped shark swimming below. A perfect end to a great day in the water.

With the boat now through the strait and on the other side of Waigeo, we continued out to sea. A gray storm appeared on the horizon and the winds whipped up whitecaps, as a light rain began to fall. As dusk began to set in, we anchored up by a small island with a shallow turquoise bank extending outward. Most of us grabbed some beers and stood on the port side of the deck as darkness swallowed the seascape, and turquoise turned to indigo, and then black.

There were two smokers on board. That in itself was unbelievable to me, given that what we were doing required a healthy lung capacity, but even worse, standing on the deck this evening, I saw them flicking their cigarettes into the water. How could they do this in such a paradise? I debated scolding them for it, knowing that I couldn’t really control their behavior and we had to try to remain on good terms for the week. A few days later one of the smokers caught me glowering at him as he tossed his butt overboard, and said that he would ash them inside, but Rod just tossed the butts overboard anyway. The toilet also flushed directly into the sea. Perhaps there was nothing else to be done with all this trash anyway, as waste management in Indonesia is not well developed. Besides the waste we generated, much more had floated in on ocean currents, especially plastics. It clung to reefs and collected on beaches. It was shocking to see, given our remote location, that so much garbage could find its way here from hundreds or thousands of miles away. But that may just speak to how much is now in the ocean.

There was talk at dinner about going on a night dive. Kwab was hesitant for safety reasons, but this place was rumored to have phosphorescent plankton. I had seen glowing plankton once before, in a lagoon in Mexico. They light up when “agitated”, as they are when an object moves through the water they inhabit. This creates the magical effect of tiny white sparks glittering away from a hand (or anything) as it waves through the water.

Of course we ending up doing it. A paddleboard was floated out and a dive line attached, dropping down to the bottom. Anyone performing a dive would attach it to an ankle and swim down, though we ended up going in groups.

I dove in and, peering into the watery darkness, was immediately awestruck. I swung my arms back and forth and watched them become enveloped in white pixie dust, far brighter than anything I had seen before. Watching others swim through the water was even more amazing. We thrashed around like swirling comets, every inch of ourselves in the water activating the phosphorescence.

I asked if this would show up on camera, and Gen, the most Zenlike member of the group, replied that it wouldn’t, “this was just for us.” There was something of a relief in that, not to have to take photos. I really enjoy taking and sharing great pictures, both for the creative accomplishment but mostly to remember a special place and time to which I may never return. But it is also a burden, when they don’t come out, the camera breaks, or I get distracted from enjoying the moment itself.

Gen was the only one to bring an underwater light, as I had lost mine a few weeks ago. Diving down, he shined it into the black depths, looking for whatever would appear, if there was anything to see at all. The light itself revealed nothing, but when he switched it off, I noticed a few faint green points of light below. These were apparently a kind of shrimp that glows, but only when it’s first exposed to light, just like glow-in-the-dark toys! Diving down to meet them at eye level, I waved the flashlight back and forth, and turning it off, I looked around. Dots of light from the plankton shone like stars, with green orbs from the shrimp like planets among them, all against the black infinite abyss of the ocean. I was in space.

The boat started up at first light, and I was awoken by Kwab as we crossed the equator. The boat stopped, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, and we were instructed to suit up. We were here, at the equator, as part of an important ritual – to appease the gods for good weather by flapping around like a sea lion on top of the stand up paddleboard, fins on and everything. And so each of us did just that. My performance was so enthusiastic that I cut my forehead on the paddleboard as I swum up from the depths and tried to land on top of it, just like the seals at Sea World. This must’ve angered the gods, as my luck wore thin later that day.

I got increasingly nervous about using my phone as an underwater camera. At our first dive site, a gorgeous white sand beach with coral spreading outward across a shallow lagoon, I lightly dipped the camera in the water to test it. Looked dry inside. Then I took off swimming, and checked it again.

The case was full of water.

Water had flooded through the bezel of the screw-on lens, which I had unscrewed earlier, cleaned, and re-screwed on, making sure it was tight – but that doesn’t matter if it’s crooked. I frantically got Kwab to take me back to the boat to get the phone in a box of rice, but with salt, it really doesn’t matter. The phone was ruined, as was my ability to take good still shots. I still had my gopro, but it’s not great at still photography and I’ve never been able to get underwater video to be anything but constant shaky-cam. So this was definitely a test of “being in the moment” and continuing to enjoy this beautiful place without worrying about the mishap with the phone – not an easy thing for me.

Fortunately there were plenty of distractions underwater. At this particular reef, Gen pointed out some blacktip sharks behind me, probably the closest I’d get to these elusive and superfast reef sharks the whole trip. And then Kwab took pictures of us floating next to the biggest giant clam I’ve ever seen – big enough to close on your arm and keep you down, as the old sailor’s tales say!

Sitting in the cockpit as we motored on, I half-listened to Kwab give me freediving lessons, still regretting my mistake with the phone earlier that day. We were approached Wayag, the crown jewel of Raja Ampat – a “postcard destination”, so to speak. Here the attraction of the above-water landscape was just as great as what life lay below. The entire island is built from chains of those same strange, steep limestone hills we encountered earlier – but arranged in a rough circular pattern, forming a massive lagoon in the middle. We entered the lagoon and anchored on a small beach, remote and untouched…except for the loads of washed up plastic.

There was time for one more snorkel that day, and we took off in the tinders for a rocky island just outside of the inlet we entered through. Here, amongst some fairly deep coral gardens, Kwab waved at us, having found two spotted eagle rays! I looked under and immediately dove after them, Gopro in hand. Of course, my approach scared them off, and I could feel the others glowering at me through their masks as I surfaced. Kwab and Patrick, the assistant dive instructor, told me to wait underwater for the fish to come to me – a tall order for freediving, especially when it takes a deep dive to achieve neutral buoyancy (neither floating nor sinking). I gave it a shot, though, diving down to a large outcrop of coral at a depth at which I stopped floating up – and, while sitting there underwater, a pufferfish I had been stalking ended up circling around me! So there’s something to the “watch and wait” technique, though without being able to breathe I could never wait for too long.

Back at the anchorage, we set up a table on the beach and had dinner there as night fell over the lagoon. It was nice, but an odd feeling, to be on dry land again.

More dry land adventures were in store for the next day, which included a hike to the top of a pinnacle in the center of the lagoon. We took the tinder to one of the countless white slivers of beach that hugged the bays and coves formed by the island towers. Here was a steep trail up jagged, knife-sharp exposed limestone, through the jungle to a “million dollar view” of the lagoon and surrounding islands. The sun had still not come out to reveal the bright turquoise color of the water in its full glory, but even so, it was a spectacular place to be. After some rather precarious group photos and selfies, we headed back down and snorkeled for a while off the beach, amongst mostly dead coral in the lagoon. As pretty as it was from above, all around the lagoon the coral condition was worse than around the islands in open ocean. Perhaps the shallow, still water inside the lagoon warmed up too much? It’d have been nice to have a scientific explanation for this and many things on the trip.

After lunch back on the boat, we headed off again to snorkel in an inlet of the lagoon at the incoming tide – when water was pouring in. We motored down the calm water of the channels, approaching the edge of the lagoon’s reef upon which big ocean waves crashed and foamed. Using the tinder, we took successive trips up the inlet channel, diving in, and shooting through on the strong currents. Gen suggested we get into formation “like jet fighters” and fly down the channel underwater. As with other parts of the lagoon, the coral was not in great shape – but here and there, a small crown of hard coral would house a tiny school of colorful guppies and cichlids.

Rod had been gathering plastic on our anchorage beach to burn. It’s generally not the best way to dispose of it, but on such a remote island there are really no other options. Later that afternoon, he found a sea turtle, wrapped in plastic on the beach, and cut it free to let it swim away. Rod had a few nutty ideas, but speaking to him later about the plastic problem, he brought up a really good point that until plastic pollution becomes regulated, this is a problem that will only get worse. “Awareness” campaigns and boycotts will simply not affect enough change. In fact, it was the plastic producers themselves, Rod claimed, that pushed the narrative that it was the individual consumer’s responsibility to fix plastic pollution.

I considered this idea. While personal responsibility for one’s waste generation is undoubtedly a good thing, continuing the narrative that this will actually make any real difference may do more harm in the long run by allowing inaction on the industrial scale. It reminded me of the signs at every Florida state park with a spring, informing the visitor to be careful of how they wash their cars, among other things. Meanwhile, the same state allows unlimited use water permits to gargantuan cattle ranches, diminishing spring flow. Algae-feeding nitrates from cattle waste seep down into the aquifer and choke the springs with green slime. What is the effect of suburban car washing on the springs compared to this?

“Be the change you want to see in the world”, they said. We need a new fake Gandhi quotation.

The sun finally came out from under grey, cloudy skies early the next morning as our ship left the lagoon, heading out to sea once more. But we made the most of the nice weather with one more stop in the Wayag archipelago, at a rugged seamount with steep walls, great for deep dives. A dive here was followed by slowly rising back to the surface while observing the life on and around the wall – corals, wavy white sea fans, sponges, and swarms of schooling fish swimming past and sometimes enveloping us. Particularly nice was to see all of this in the morning light, a rare thing in such a cloudy and rainy climate.

We putted along back to the south, more or less the same way we came to Wayag. Inter-island journeys were a nice break from all the action, especially on sunny days like this one. Often, I’d wish they’d last longer, so I could read my kindle somewhere on deck while the trimaran cut its foamy path through the blue ocean, lightly bobbing on small swells while I watched distant islands come into view. One particularly large island along this path had a massive, rainforest-clad mountain reaching up through the clouds. No one knew what it was called or if anyone lived there. With no internet to tell me otherwise, I imagined it to be a terra incognita of lost tribes and strange creatures, in the grand tradition of Robinson Crusoe and King Kong.

But anytime I’d get too lost in a reverie, the boat would slow down on approach to a new island, and it’d be time to suit up. This time, we stopped at a crescent shaped island with a gorgeous stretch of white beach (at a distance…this one was apparently strewn with plastic, too!). A narrow channel divided the island in two, and here we repeatedly hopped in at the far side of the channel from the sailboat. Diving down at a depth of maybe 15 feet, there was a very strong current that shot me like a rocket through the passage, past mounds of pretty hard corals perched on the shallow slope of the nearby island. It made the inlet drift dive seem like a lazy river.

There was another site in this area Kwab wanted to check out, but he wasn’t sure if the tides and currents would render it safe to dive. It was a rocky outcrop at the end of this long island. He and Patrick jumped in and checked it out. We were good to go.

Next to the larger outcrop was a tower of rock rising fifty or sixty feet from the bottom and narrowing at the surface. Kwab dove down, and we waited…and waited. He appeared again fifty yards away – having swam through a tunnel! Of course we had to follow. I dove straight down, to try to get depth as fast as I could. I looked around for openings – was this it? I swam into an alcove which turned into a short tunnel and then opened up into a crevice – completely filled with big yellow fish! I was in “fish soup”, the term divers use to describe when a school entirely surrounds them in a sphere of fish. I never could quite get that to happen, out in the open – but here, they were all around me, and not afraid of being so like they usually are.

This site traded corals and colorful, tiny reef fish for big schools of big fish – some yellow, some blue with yellow trim, some silver, all moving around quite fast except for the ones lazing in the tunnel crevices. Rocky promontories like this made for a different dive experience than the shallow, sandy coral beds we saw elsewhere – or even the coral covered walls we had seen earlier in the day.

Kwab *somehow* found another tunnel, completely invisible from the surface and not at all obvious even at its entrance, which looked like a small indentation, not a tunnel – but peering in, there was a light on the other side – and a long, dark, and tight path to get there. Whew! After a claustrophic swim through I decided to stick to the ones with fish.

At the end of this seemingly neverending dive, (try doing that with Scuba!) Toni spotted a manta, the mythical gigantic ray we had all been hoping to see the whole trip. We all followed, and I barely saw the white spots on the ends of its fins, far below. But a sign of things to come, perhaps?

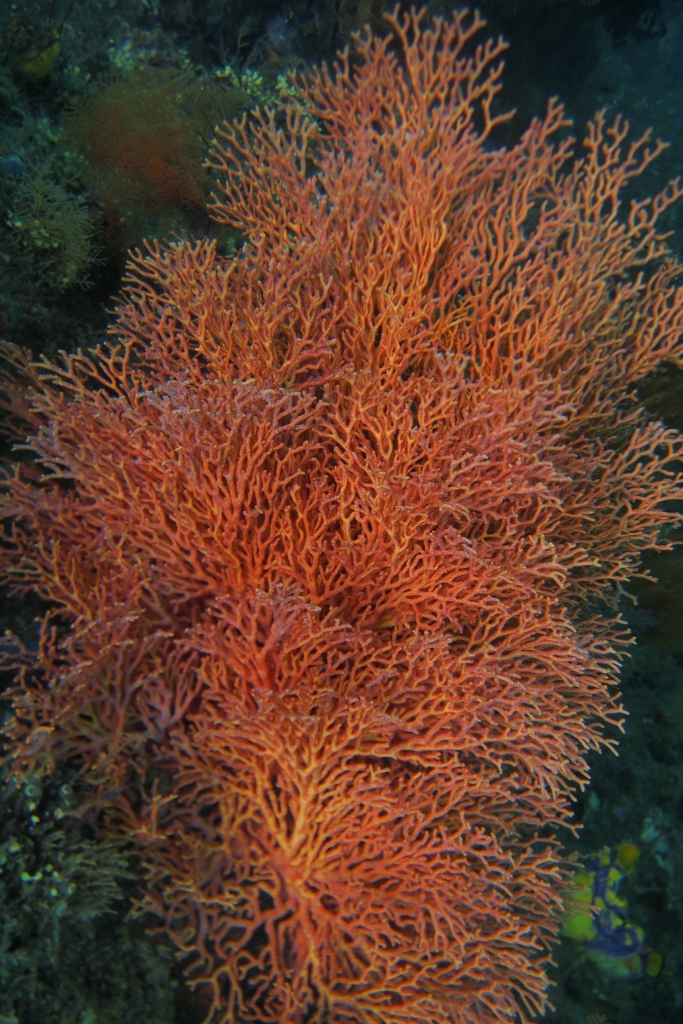

Back on the boat, we ate a well-earned lunch overlooking the white crescent of beach, having spent hours in the water already. But we weren’t finished yet. As clouds began to roll in to end a blissfully sunny day, we found our anchorage for the night at the mouth of a short channel dividing two islands. Time to hop a final time on this longest day of freediving, as there was a wall of diving to be had along the edge of the cliff forming the far side of the channel. Between the increasingly gray skies and a natural green murkiness to this water, it was a bit hard to see – but this was a pretty cool site nonetheless, with a wide variety of corals, sponges, sea fans, and anemones – including a creature consisting of white feathery tendrils that stings (found that out the hard way). I did try my very best during the whole trip to never touch anything living. Also notable among these were soft corals – the first time I had seen these since I had been in Thailand. Hard corals are stony structures, the skeletons of dead polyps that form brittle branches, spikes, and domes. I don’t know how soft corals are formed, but they form a softer, bulbous structure that is usually a vivid red or purple – at least the ones I was seeing. They’re beautiful, but rarer than hard corals – I had never seen one before coming to Asia.

The tinder was coming around to take us back. Time to go – the wind was picking up and more clouds were blowing in. Back on the ship, we battened down the hatches, but fortunately the storm wasn’t worse than a little wind and rain.

I got out of bed early enough to take the stand up paddle board for another spin. This time I explored the other side of the channel, paddling over glassy, shallow waters in the humid, still air of a quiet morning. I could see what looked like some nice coral from above, so I stuck my Gopro in the water at random a few times, and these actually turned out to be some of the best still photos it took on the trip. I was about to head back when they sent the tinder after me to get me in quicker.

We stopped near an isolated rocky islet after a few hours, and the weather wasn’t looking good. A front of clouds on the horizon were moving in, and the wind was already whipping up. But Kwab was determined to give it a shot here. Patrick jumped in, and immediately popped up to report on a Manta swimming below! I assumed he was kidding, but he insisted there really was one. But I began to wonder after I jumped in. Though the bottom was still visible, this stretch of water was deep, thirty or forty feet, with nothing to be seen below. The storm clouds were above us now, treading water in vain, and Kwab was just about to call it when someone saw the Manta again! We all swam at top speed over to where it should be. But then another over here! I swam back again, still not seeing them…until I did, almost by accident. It was a black creature of the deep, diamond shaped with white tips on the ends of its ten or 12 foot wingspan, a long stinger tail and mouth lobes like a giant beetle.

Then I saw another, and another, and these were even bigger…at one point I counted six monster Mantas in the same place, swimming below, crossing paths as they cruised in various directions, each gigantic fin ever so slowly flapping through the currents. Of course I had to dive down to meet them, but easier said than done – I remembered what Kwab taught me about not chasing the wildlife, yet it was too deep to just go down there and chill, in hopes they would pass by. I tried though. Spotting one, I anticipated its path, and dove down to look it in the eyes, while carefully trying to keep my distance. But the Manta saw me, and like some kind of massive spaceship from Star Wars, slowwwllly pivoted around to swim away. I had better luck swimming with a manta. I had to kick hard to match its pace while I submerged myself, at a gradual decline so as not to scare it. And then, as my lungs were near to bursting, there I was, swimming right alongside a Manta Ray!

Turns out, Kwab knew this was Manta Ray City, but was keeping it on the DL, so we’d be surprised. I certainly was.

We motored on for most of the rest of the afternoon, heading south. The skies were still gray and overcast at our stopping point, which is a shame – a little sun would’ve been amazing to light up what turned out to be the most amazing hard coral reef I’ve ever seen.

I’ve talked a lot about “coral” in this absurdly long account without describing it in any particular detail. Hopefully these videos have helped with that. Coral reefs are a rare and dying ecosystem that is probably going to be completely extinct (with some weird exceptions, like deep sea corals) with a few decades. Perhaps it’s this fleetingness that makes them special to me, like a solar eclipse. But a “coral garden” can also be a beautiful landscape of strange shapes and colors of the coral structures, like something out Dr. Seuss, with all manner of secondary life hiding among them, such as anemones, sea fans, giant clams, and of course, a diverse array of fish, from the smallest larva, to the biggest fish, whale sharks, who consume coral spores in spawning season.

Raja Ampat is the center of coral diversity in the coral triangle, the center of coral diversity in the world, and this place must have been the center of diversity in Raja Ampat. Every type of hard coral I’d ever seen seemed to be present, from a brain coral literally the size of a house (including a secondary coral garden growing on its crown) to small, spiky corals colored a brilliant violet-blue (which Toni later told me is the coral polyps’ last gasp as they are bleaching…thanks Toni).

I’ll let the videos do the rest of the talking here.

We parked there for the night. In the morning, I rose to look out from the stern deck to see Gen paddleboarding across the lightly rippling waters of the reef lagoon, illuminated orange with the rays of the rising sun. I considered joining him, but it was soon time to go.

I had been told this was strictly a freediving trip, but today those who wanted to scuba dive were given the opportunity. I believe I was the only person on board without a certification, but fortunately I wasn’t left stranded – after the scuba boat picked up everyone else, Kwab, Pierre, Gen, and I went off on our own.

Our destination was not as remote as some of the others – it was a pier busy with daytrippers gathering on docked boats. Despite all this activity, the snorkeling just underneath was pretty darn good. I counted about 10 different species of parrotfish (unless their different colors were due to sexual dimorphism) including giant bumpheads. Pufferfish, lavendar-colored grouper, even a sea turtle – the gang’s all here. Attached to the pilings were bright purple soft corals, and an almost unbelievably healthy reef of hard corals hemmed in by the square-shaped pier structure. How could this reef, with so much human activity surrounding it, thrive while the one in the Wayag lagoon, a paradise beyond imagination in the middle of the ocean, was dying?

The reef continued beyond the pier, gradually sloping down into a deep strait between islands. I saw a scuba diver with a huge camera set up, complete with unwieldy flash attachments. He was jamming it into a clownfish-inhabited anemone to get that perfect shot. I can relate, but how ironic it is to damage the very thing you’re trying to see in its natural state. This is, however, a dilemma that anyone visiting this reef will face. You’ll bump into something, inevitably. And then there’s just getting here on an airplane, which contributes to climate change, the very thing that will cause the eventual extinction of most coral reefs this century. If you’re here though, at least be respectful. It’s good karma, for whatever that’s worth.

We returned to the ship for lunch before heading out on an afternoon excursion. We passed everyone else coming in on the dive boat as we departed. Apparently they saw a manta pass above them, which is something of a holy grail in these parts (double points for a solar manta-clipse!). We would not be so lucky.

We arrived at a site with strong currents, and Kwab decided he’d check it out first to see if diving there was feasible. But this apparently wasn’t communicated to the crewman driving the tinder, who took off the moment we dipped our heads in the water. Naturally, it turned out it wasn’t safe to dive there, and also, we were stranded. Kwab decided we’d swim along the coast to a nearby dive resort. It was a long haul, with nothing but fields of dead coral along the way. We clambered up on the dock and wandered around, but a staff member there had no use for a bunch of Robinson Crusoes, and tried to kick us out. What were we going to do, swim away into the great blue yonder? I let Kwab argue with him, but before long, we spotted the tinder buzz past the bay. We waved and shouted to get his attention, but he kept right on, oblivious, no doubt beginning to believe we had drowned. I let out a single bellow loud enough to scare the fish, a bit of frustration at this point helping with the volume. That finally got his attention, and he took us back…where we heard all about the awesome manta-clipse. Sigh.

Our port-of-call on this final night (can you believe it?) was the dock of a small island just big enough for a quaint fishing village, refreshingly outside of the tourist economy. It was a very Christian town, with Christmas decorations still up on this day in mid-January. We wandered around the neatly-groomed sand streets at dusk as children followed us around, while wind whispered through the town’s palm trees, far more numerous than its houses. After so many uninhabited islands, it was nice to see how the people of Raja Ampat lived. I loved how their town was so gracefully but casually embedded in one of the most beautiful natural places on earth.

We had one last dive site to visit on Sunday, and Kwab promised it wouldn’t top everything else we’d seen so far. Ah well – grand finales are overrated anyway. Instead, it featured a combination of elements from many previous dive sites.

We stopped at a small, unassuming rocky islet just big enough to have a few stunted shrubs atop it. Though the shallow waters around us were calm on this sunny day, the current was running strong. This would be a drift dive. I zoomed towards the islet, underwater, and past a gorgeous mound of coral before making a hard right into a little cove formed by the islet and its surround rocks. Under these rocks was a neat little tunnel that we swam through – and on the other side, open water and a raging current over another bed of coral and swarms of small fish. Kwab pointed out a nudibranch clinging to a rock. Also known as sea slugs, these are colorful little worms that grace coral reef landscapes. This one was no larger than a caterpillar – amazing he found it.

Don’t miss the shark at 0:25 in the video below!

All in all, a nice spot to wrap things up. And then it was time to go back.

From that point on, I just lived my first two days in Raja Ampat in reverse. We disembarked and unloaded the boat at the scuba village dock in Waigeo; took a caravan of SUVs to the ferry; traded photos on the two hour long ferry ride; checked in to our respective hotels in Sorong (this time, I booked a somewhat better place with a working toilet); got back together for one last dinner (after a wild goose chase around town in a taxi going the wrong way); and the next day flew out from the airport, a vaguely dystopian facility with every TV running goofy, bizarre ads nonstop for the same local bakery that probably bankrolled it.

And I was away. Off to Bali, and new adventures with new people, for another two weeks before leaving Indonesia altogether.

Raja Ampat has stuck with me. It’s a place of profound marine diversity and otherworldly natural landscapes, all wonderfully away from the grind of the human world and all the destruction it brings. And yet that human world is encroaching, and signs of its destructive force are everywhere; from floating plastic, to netting and other trash wrapped around the reef and washed up on the beach, to the white skeletons of coral that have bleached due to warming seas and ocean acidification.

I could end this with a call to action, and sure, do your part to reduce your plastic and carbon footprint, especially while you’re actually visiting a place as sacred as Raja Ampat. But the rest of the world will not follow your example, and these problems will get worse before they get better. And so, I am privileged to have witnessed this future paradise lost while it still exists in the full glory of its amazing biodiversity.