A páramo is an uncommon biome and ecosystem that is only possible with the combination of a moist, tropical climate with a very high altitude, well above the tree line. The result is a starkly beautiful moorland inhabited by plants and animals that are uniquely suited to the harsh environment of alternating intense tropical sun and frigid nighttime temperatures in thin air.

By the strictest definition, páramos only exist in the tropical Andes from Venezuela to Peru, although similar environments exist from Hawaii to Kenya to Papua New Guinea. I visited two Colombian Páramos: Siscunsí-Ocetá Regional Park, northeast of Bogotá, and Sumapaz National Park, just south of Bogotá and containing the most extensive páramo in the world.

Though they can rapidly heat up when the sun comes out, páramos are often foggy, misty, and cold, as it was upon our arrival to Sumapaz. This creates a mysterious, even eerie atmosphere over the desolate moor landscape, inhabited only by the shadows of frailejónes, thick-stalked shrubs related to the sunflower that are iconic of the páramo environment.

The afternoon sun finally melted this fog away, revealing the rolling hills and lakes of the Sumapaz Páramo.

Like most rare environments, Páramos are worth preserving for the sake of the animals and plants that depend on them, as well as their intrinsic value. But they also play a vital role for nearby human communities. The almost-constant rain that falls on the Páramo is absorbed and filtered by the moss-covered soil, providing an enormously important source of water for nearby cities – 80% of Bogotá’s water comes from the Chingaza Páramo just east of the city. This role is immediately apparent upon the first step onto a Páramo – water squeezes out, exactly like a giant sponge. This absorption of rainwater also provides an important buffer against flooding.

As with a rainforest, numerous plants from the páramo are important sources of traditional medicine. Some of these, such as a shrub called sanalatodo, have also worked their way into scientific research, in efforts to isolate the beneficial compounds therein.

Despite human reliance on the Páramo, these biomes still face eminent threats of human origin, such as mining and climate change. Sumapaz is being prospected for oil reserves, while a gold mine is being planned at another páramo, Santurbán. This could directly lead to the introduction of cyanide into the water supply of nearby communities.

Meanwhile, warmer temperatures and alternating droughts and deluges as a result of climate change are expected to have a damaging effect on the fragile páramo, which a study found is likely to increase the risk of flooding.

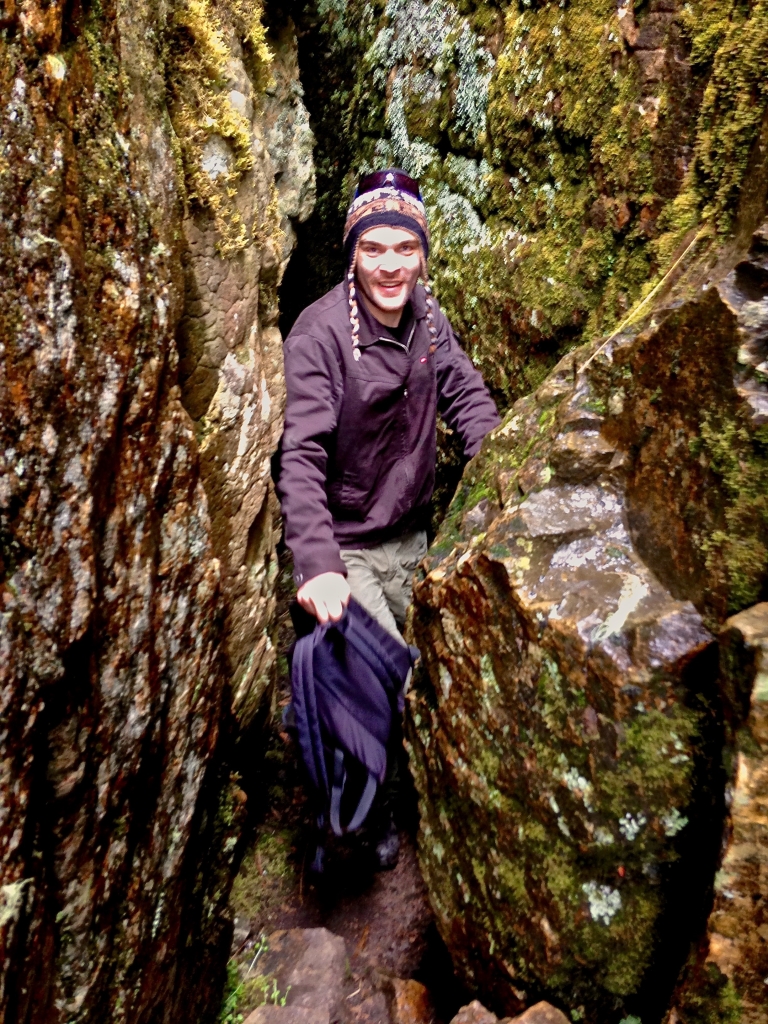

I later visited Páramo Ocetá, climbing up from the ridiculously charming, almost half-a-millennium-old town of Monguí. Here, the clouds never really cleared up – in fact, they only gave way to rain at about midday, turning the meadow-like páramo into something more like a bog. But we could still see enough to tell that this place had a different landscape – unlike the rolling hills of Sumapaz, Ocetá had rockier promontories, cliffs, and narrow gorges, one of which we needed to squeeze through to continue. Through the mist, we could see the frailejónes standing atop the cliffs, giving me the spooky sensation of being watched by silent guardians of the páramo.